If African literature has often been forced to look back, Will This Be a Problem? The Anthology: Issue V feels like a collective decision to do so while looking forward, to chart futures that are wholly our own as Africans.

By Frank Njugi

In one of the decade’s more transcendental African essays, “Africanfuturism: A Literary Plane of Infinite Possibilities for Africa’s Future”, Afrocritik’s Chimezie Chika makes a point that feels less like an argument and more like a tapping on the continent’s shoulder. Africanfuturism, he suggests, is not merely a genre but a provocation — a way of coaxing the mind to stretch beyond the comfortable myths of ancestry and into the harder, more elastic questions of what comes next.

For so long, our intellectual energy as Africans has been spent excavating the past. And yes, there is beauty in that archaeology, a tenderness even. But Chika insists that memory alone cannot hold the weight of a continent’s imagination. The real challenge — the one we have tiptoed around for decades — is to stand in this uneasy present and hold both directions in our line of sight. To interrogate the past not as a shrine but as a compass. To let the future glare back at us and ask who we think we are becoming.

It is the kind of thinking that feels almost dangerous, which is perhaps why it is overdue. And like all great cultural provocations, it leaves you with the electric feeling that the work of imagining Africa — not as a wound or a romance, but as a possibility — is only just beginning.

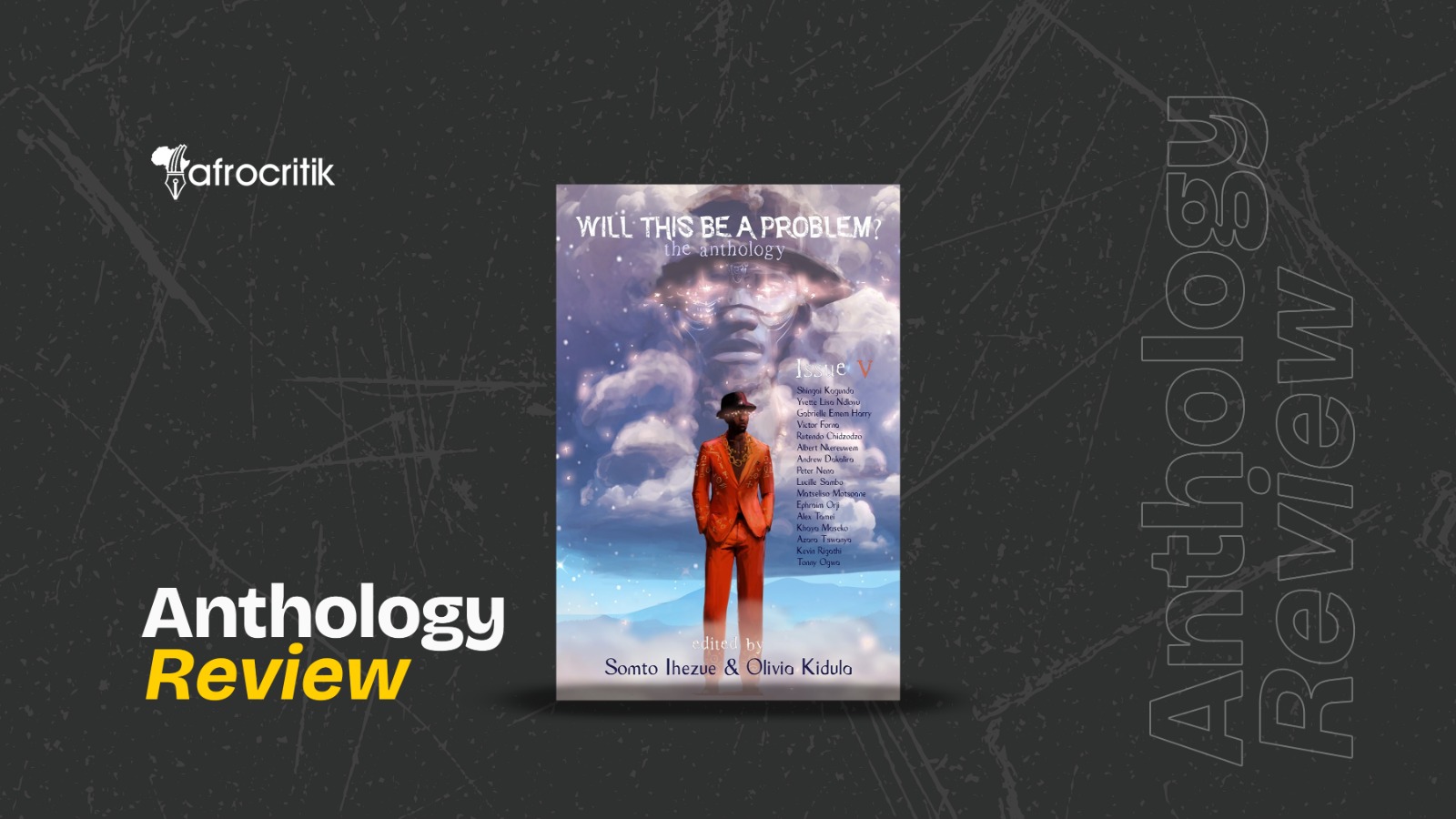

In East Africa, the work has not been waiting politely; it has already begun. And in many ways, the most intriguing hands shaping this belong to Will This Be A Problem?, a literary journal that has been rewriting the coordinates of African speculative writing since its scrappy 2014 beginnings.

What started as a niche refuge for the oddball, the dreamer, and the speculative evangelist morphed, by 2025, into one of the continent’s sharpest engines of imagination: a place where science fiction, fantasy, horror, and the whole unruly cosmos of African fantastika were not only welcomed but treated as serious cultural inquiry.

Now an imprint of Shilitza Publishing Group, the journal doubled down in 2025 with Will This Be A Problem? The Anthology: Issue V, a fierce, sixteen-story dispatch from writers across the continent and its sprawling diaspora. If African literature has often been forced to look back, Will This Be A Problem? V — The Anthology feels like a collective decision to do so while looking forward — to chart futures that are wholly our own as Africans.

Among the sixteen stories, Shingai Kagunda’s “The Language We Have Learned to Carry in Our Skin” takes the old colonial hangover — that cocktail of corruption and state-sanctioned amnesia — and mutates it into something feral: parasitic beings burrowed beneath the skins of Kenyan politicians, a grotesque inheritance passed down from white colonisers who knew exactly what kind of monsters they were breeding.

Fellow Kenyan Kevin Rigathi’s “If Memory Serves” is the kind of story that toys with you in the dark before letting you realise it has been rearranging the furniture in your head the entire time. You finish it and feel compelled to circle back to the first sentence, suddenly aware that everything you thought you understood was a decoy. Rigathi imagines a future where forgetting has been privatised, packaged, and pushed to market like a miracle cream. A sleek corporation has figured out how to mass-produce a memory-wiping procedure, then flip those extracted memories into high-end commodities for the rich — a powerful lesson and reminder that the further we drift from memory, the less human we become.

Tonny Ogwa’s “The Clans”, on the other hand, goes for a more combustible canvas. He imagines a Kenya where the Luo people did not merely resist the early missionaries but expelled them outright, long before colonial armies could arrive. What unfolds is a world in which Western faith slowly siphons the ancestral power from the very bodies that once held it — until the communities decide enough is enough.

West Africa, long the continent’s most confident engine of speculative firepower, shows up here exactly as expected. Nigeria’s Ephraim N. Orji’s “The Sirangori Fey Market” is a grief-charged tale in which a parent, undone by the loss of a daughter, steps into a marketplace that feels less like a location and more like a living riddle.

The choice of the market is perfect, as across the continent, markets are the true parliaments of daily life. Orji takes that familiarity and makes it strange. What begins as a richly textured tour of its wonders and terrors quickly becomes something more acute: a hunt.

Sierra Leonean writer, Victor Forna’s “Mr. Original Swag” is a deal-with-the-devil story dressed in the bright, mischievous voice of a narrator who keeps insisting you shouldn’t trust a Mr. Swag — which, of course, means you lean in closer. Forna pushes the tale beyond mere cautionary folklore, staging a cosmic TV show suspended somewhere between time and whatever lies beyond it, where gods don’t love or loathe us; they simply toy with us for sport. The result is a story that keeps shifting its centre of gravity until you realise you have been watching a trap spring shut in slow motion.

Another Nigerian, Gabrielle Emem Harry’s “Something Cruel”, moves differently: tighter, hotter, like a fuse burning towards a secret. From the opening paragraph, Harry plunges the reader inside Minika’s trembling perspective — a warrior crossing The World Invisible in search of an escaped punishment who may be wearing the wrong face. The air around her feels fatalistic, and Harry’s prose turns every sensation into an omen. The story swerves into the unexpected but never loses its emotional voltage, becoming a vivid meditation on vengeance, mercy, and the ways our private hells echo one another without our knowing.

One thing the anthology makes impossible to ignore is the editorial intelligence behind it. Somto Ihezue and Olivia Kidula understand something many pan-African projects pretend to know but rarely honour: that a continent of fifty-plus nations and its sprawling, restless diaspora cannot be represented by the usual handful of literary “heavyweights”. They refuse the lazy seduction of letting the same familiar voices carry the book. Instead, they widen the aperture until the full sub-Saharan speculative stratosphere surges in — East, West, South — all humming at different frequencies, all necessary.

From the South, Malawi’s Andrew Dakalira brings “Ash Baby”, a story that feels almost cinematic in its scale: a cosmic battle cracking open reality like a windowpane hit by too much light. Dakalira’s reverence for African spiritual traditions sits beneath the chaos, reminding you that the supernatural in our stories is rarely a departure from belief but an extension of it.

Lesotho’s Matseliso Motsoane takes a different tack in “Baby Potion”, perhaps a quieter but no less compulsive piece. Lebo, desperate to conceive, moves through a world where whispers travel fastest through the hiss of hairdryers and the rhythm of braids being tightened. Motsoane turns the beauty salon into a kind of informal intelligence agency — a place where truth, suspicion, and female intuition collide. Is it her husband? Her mother-in-law? A rival woman meddling with biology or magic? The story carries the intrigue of a domestic thriller but lands somewhere more surprising, more playful, and more thoughtful than the setup promises.

Even the apocalyptic gets its moment in Zimbabwean revered writer, Yvette Lisa Ndlovu’s wicked little gem, “Dinosaurs Once Lived Here”, where the end of the world arrives courtesy of the forgotten descendants of those Noah left behind to drown. Narrated by Anansi’s cousin, the god of drunkenness, the story suggests that what survives catastrophe is not purity or righteousness but the myths we have carried all along.

Her compatriot, Rutendo Chidzodzo offers “I’m Home”, a brief but resonant meditation on grief and transformation. A child is taken by a njuzu, and what unfolds is less a rescue tale than an aching reflection on what happens when someone is altered by forces beyond the familiar, returning home with edges that no longer fit the old container.

If there is an anthology this year that earns the right to stand not just proudly but centrally in the conversation about what African literature needs right now, it is Will This Be A Problem? The Anthology: Issue V. And that has little to do with sentiment. It earns its place through sheer craft, from the words themselves to Peter Marco’s arresting cover art.

The anthology’s power lies in its curation, in the way Somto Ihezue and Olivia Kidula assemble a full-spectrum experience of the continent’s imaginative terrain. The stories move across time, faith, grief, futurity, and cosmology in a way that feels like a deliberate journey through the past (not as shrine, but as instruction); through the strange; through the volatile present we are still learning how to inhabit; and into the unanswered, necessary questions of Africa’s future.

And perhaps that is the thesis of this contemporary genre; that imagining the future is not escapism but a political, cultural, and spiritual act. This anthology understands that and insists on it, page after page.

Frank Njugi, an award-winning Kenyan Writer, Culture journalist, and Critic, has written on the East African and African culture scene for platforms such as Debunk Media, Republic Journal, Sinema Focus, Culture Africa, Drummr Africa, The Elephant, Wakilisha Africa, The Moveee, Africa in Dialogue, Afrocritik, and others.