There is a way to portray sexual violence onscreen, even in Nollywood, and that way does not involve reducing it to a mere exploitative plot device.

By Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku

Nollywood just released a new Madam Koi-Koi adaptation. Ms. Kanyin, they call it, a somewhat clever play on the mythical “ghost” teacher’s name, if you pronounce it right. Of course, the new film brings back memories of the previous adaptation, The Origin: Madam Koi-Koi (2023), with conversations about which one is the better adaptation. But I’m more concerned about a troubling trend that both projects exemplify, although to varying degrees: the reckless and irresponsible use of sexual violence as a plot device in Nollywood.

Criticism of the portrayal of sexual violence in fiction has been a recurring conversation in cultural discourses, especially in literature and film. In film and television, the conversation is more prevalent in Hollywood. As far back as 1973, The New York Times published an article titled “Rape—an Ugly Movie Trend” where rape was described as “the new Hollywood game”. But in the last decade, practically every culture publication in Hollywood has had something elaborate to say, much of which was inspired by the critically acclaimed, fan-favourite Game of Thrones (2011) which received some backlash for its many, many rape scenes.

“How Much Rape Is Too Much Rape on My Favourite Shows?” read a 2015 Vulture piece inspired by the HBO series. And in 2016, Variety published a deepdive into “The Progress and Pitfalls of Television’s Treatment of Rape” where Maureen Ryan, a TV critic, discussed her research findings to the effect that even TV writers and showrunners were experiencing fatigue with sexual violence as a go-to plot device.

From Glamour, which published an article titled “I’m Tired of Male Screenwriters Using Rape as a Convenient Backstory for Women” to The Guardian which has had at least four publications on the subject in the last decade, so much has been written in Hollywood that not much is being written anymore. And, perhaps, there is no longer much of a need to. While there does not seem to be any published data to support it, sexual violence as a plot device does appear to have declined in Hollywood (although the conversation recently resurfaced with the release of Celine Song’s Materialists (2025)).

At the very least, the conversations got the Game of Thrones creators to commit to changing the show’s approach to sexual violence, and Hollywood actor, Kiera Knightly, who notably avoids “films set in the modern day because the female characters nearly always get raped” has had to admit that there’s been some improvement.

The reasoning behind the conversation is not difficult to grasp. Using sexual violence to create conflict or propel the plot decentres victims, and can trigger them, trivialise the trauma they experience, and perpetuate harmful stereotypes about abuse. How sexual violence is portrayed in art can and does have an effect on individuals who have experienced sexual violence as well as on the collective psyche.

In 2015, Joanna Bourke, an American academic, warned that the use of rape as a plot device is shifting sympathy from the victim to the perpetrator. And in 2022, RAINN, the largest nonprofit anti-sexual violence organisation in the United States, told Vanity Fair that the organisation gets an uptick in calls to its support hotline after rape content is aired. American psychologist, Patti Feuereisen, who specialises in treating rape survivors, also has people reach out to her after they’ve viewed sexual assaults onscreen. “The survivor may relive her abuse”, Feuereisen explained to Vanity Fair, also noting that trauma symptoms may return.

If that’s the situation in the US, where there is manifestly more access to help for victims, as inadequate as it is, how much worse might it be for people in Nigeria, including girls and women, who live with these experiences and have to deal with casual and triggering portrayals onscreen over and over again? But Nollywood does not seem to care. In fact, the problem seems to be getting worse. And it’s not as if critics have been completely silent.

Many Nollywood projects have been criticised over the years for their problematic approach to rape and sexual assault in films. In a review of the earlier Madam Koi-Koi adaptation, The Origin, Carl Tever wrote somewhat extensively on the film’s “graphic abuse in addressing femininity and women’s bodies”. In a recap of Nollywood Film Club’s conversation on the film, Ikeade Oriade noted that we were once again reminded “that Nollywood films have a sexual assault problem”.

Daniel Okechukwu dug deeper into the problem as a symptom of the male gaze in an In Nollywood essay on the film where he asked, “When a male director shoots a rape scene, who does he shoot it for?” And reviewing the same film for Afrocritik, Seyi Lasisi described the film as treating sexual assault casually, citing other films such as Hey You (2022) and A Young Time Ago (2023) as films with the same flaw.

Personally, I’d already written a scathing essay in 2021 about the Nollywood comedy, Dear Affy (2020), and what that film says about Nigeria’s rape culture. And in my review of the Netflix series, Shanty Town (2023), a few months before The Origin, I was heavily critical of how Shanty Town reduced sexual violence to even less than a plot device. When The Origin aired, I did not see the need to flog the issue. Well, it now appears that the issue does not need to be flogged to death.

Perhaps, our manner of discussing the problem by situating it within reviews or commentaries on specific films is not quite driving the point home to Nollywood filmmakers. Maybe we are now at the point where we have to write long-form analyses like our Hollywood brethren. Maybe we now have to beg Nollywood to kill the sexual violence plot device. It is unsettling that despite the criticism for the past few years, we seem to be seeing more of it and more often, with too many instances in just this first half of the year 2025.

The latest instance plays out in Nollywood’s newest iteration of the Madam Koi-Koi urban legend. The titular Ms. Kanyin is a strict secondary school teacher with very few friends in the school community. We already expect that she will transform into the terrifying Madam Koi-Koi at some point in the film. The “how” is the question. In The Origin, sexual violence—terribly portrayed, as the reviews quoted earlier emphasise—was the trigger. Thankfully, Ms. Kanyin is more creative with its inciting incident.

However, in the course of building up to said inciting incident, the filmmakers still manage to throw in a gratuitous sexual assault scene. A parent with a powerful position privately approaches Ms. Kanyin and gropes her before making her a suggestive offer and then walking away. The man’s son witnesses some part of it, and that interaction influences further interactions between the student and the teacher that eventually play into the incident that transforms Ms. Kanyin into Madam Koi-Koi.

But that sexual assault did not have to be a part of the story. The parent could have simply propositioned Ms. Kanyin, using his power and influence against her, and nothing about the story would have changed. The student would still have treated her with disrespect and everything else would still have fallen into place.

In fairness, the film does pay more attention to Ms. Kanyin’s experience of the assault than Nollywood typically does, at least in the moment. But why did sexual assault have to feature as a plot device in this film, in the first place? There are many versions of the urban legend, but if there’s one that involves sexual violence, I have never heard it. And the adaptations tend to deviate from the source material, anyway. So, why exactly is sexual violence inevitable in the Madam Koi-Koi adaptations? Why is Nollywood so eager to reduce such a sensitive subject to a mere, unnecessary plot device?

I was first reminded of this recurring problem on my very first trip to the cinema this year. The culprit was Summer Rain (2025), directed by Adenike Adebayo Esho. A sentimental romance drama that explores young love, and the loss and rediscovery of it. The film follows two sweet and innocent teen lovers whose romance is cut short when the girl, Murewa, ends up pregnant after supposedly having intercourse with a “bad boy” boyfriend she was supposed to break up with. When the lovebirds re-connect a decade later, they expectedly have to confront their past choices if they are to have any chance at moving forward with each other. And this is where the writers run into creative difficulties.

I have written in the past about how much Nollywood loves its perfect women and punishes its imperfect ones. Ordinarily, there is no happily-ever-after for an imperfect Nollywood leading lady. And so, if the plot is to progress to a point where a Nollywood leading lady has to have a happy ending, she needs to be perfect. She has to be “a good girl”. She cannot be a person who simply makes “bad decisions”, like choosing a boy who everybody knows is bad news over her nice, caring male best friend.

As Stephanie Merry, writing for the Washington Post, observes: “Rape is everywhere on television. It’s an overused plot device, and in recent years, viewers have started calling it out for what it is: a cynical trope that’s casually employed, either to make a female character sympathetic or to spur her significant other into action, knight in shining armor-style”. And that is what Summer Rain does. It takes the easiest traumatic route in the book and revisits the lovebirds’ teenagehood where we not only discover that Murewa was a victim of rape at the hands of the bad-boy boyfriend, but we also have to watch a brutal footage of it.

It is a heavy cop-out that takes away Murewa’s agency and exploits sexual violence as a means for triggering sympathy, from both the audience and her male love interest. Without any beyond-surface-level attempt at exploring the impact of such a violent crime on the woman who experienced it, and with the focus being on the pregnancy itself and its role in separating the young lovers, it becomes clear that the essence of that graphic backstory, consciously or unconsciously, is to explain away what would ordinarily be received as a character flaw by what the film expects to be a conservative, unaccepting audience.

The essence is to sanitise the image of the female protagonist and make her “unsavoury” out-of-wedlock pregnancy understandable, heavily sympathetic, and, therefore, forgivable and somewhat acceptable to the audience and to the male love interest who now feels the need to protect her. To return her, as near as possible, to a state of perfection that would earn her the right to a happy ending as opposed to the punishment that she would be deserving of, in Nollyverse, if she had just simply made bad choices.

But before Summer Rain was released in cinemas, Awal Abdulfatai Rahmat’s Penance (2025) was released on Prime Video. The entire essence of Penance is sexual violence and its implications. So, in a way, it’s more of the plot than a mere plot device here. Alice, a young employee, accuses her employer of rape. Through police interrogations, therapy sessions, and conversations with lawyers, we learn each side of the story, from the perspective of the teller. When we’re presented with Alice’s version of events, the camera adopts a partly onscreen, partly offscreen approach, and the focus, in both the onscreen and offscreen cuts, is almost exclusively on the act and the perpetrator, and not in a decent way.

Whatever the intent was, the result is that even though the incident is captured from Alice’s perspective, Alice’s experience of it is erased, as if it isn’t provocative enough that there are any graphic details at all. And worse still, it all turns out to be a lie. We eventually come to find out that Alice set her boss up and falsely accused him as revenge for a dear friend of hers, Tyra, who had been his victim in the past, and we realise that we have been made to sit through graphic details of a rape that did not even happen. And all for the sake of dramatic tension cloaked with the veil of cinematic justice.

Then, there are the even more frustrating cases where the use of sexual violence does not so much as qualify as a plot device. Where it neither adds to the plot nor propels it. Where it happens just to happen, or at most, just to make a point that has already been made. Take for instance, Okechukwu Oku’s Blackout (2025) a psychological thriller that is similar to Penance in its main plot being centred around sexual violence, but with a unique supernatural premise.

In Blackout, Judith wakes up one morning with no memory of her husband and her children. It turns out that Judith has been the victim of a man’s obsessive fantasy, and the man who calls himself her husband actually put her under some sort of spell that tampered with her sense of identity and reality and put her under the illusion that she was married to a man who was in fact her abductor.

For the avoidance of doubt, obtaining consent from a woman by pretending to be her husband is both morally and legally considered to be rape, even more so when she has no psychological capacity to give said consent. But the sexual violence implication is not very glaring on the face of the plot, and so, it’s probably more of an unintentional portrayal than a casual one. The film itself does not seem to realise the implication, and it makes no attempt to address it beyond Judith fighting to escape when she eventually comes to.

But there is a scene, a flashback to a time right after her kidnap but before she gets locked in that psychological prison, where Judith is lying unconscious and her kidnapper gropes her breasts. That is sexual assault used as casually as casual can be, and it’s included to make a point of how perverted he is, as if that message has not already been passed by the mere fact of his drugging and kidnapping her. It’s a triggering scene that could very easily have been done without and, yet, one that the filmmakers couldn’t let go of, in pursuit of the discomfort that they were eager to trigger in the name of delivering a psychological thriller.

One of the more recent and most surprising offenders is Labake Olododo (2025), an epic film about a female warrior in an ancient Yoruba village. The eponymous character in this film is a firm, no-nonsense warlord who is initially presented as a woman who does not care much for patriarchal ideals (her eventual acts of conformity and heteromantic indiscretions are a matter for a different conversation).

In an early scene in the film, her male deputy, known for terrorising the villagers, abducts a young girl and rapes her offscreen. To Labake’s credit, when she hears of it, her disgust and anger are undeniable. Not only is she determined to penalise him, she is the only person who bothers to ask about the victim while every other relevant character prioritises the victim’s father and his anger.

But as a plot device, the rape would have led to a reaction that would move the plot along. However, nothing comes of it that actually moves the plot along. The girl’s story quite literally disappears from the film, and she’s not even important enough for her name to stick.

Labake does punish her deputy, which changes the course of the story, but not for the reasons you’d think. She punishes him for sleeping with another man’s wife and for disabling the angered man with charms. The rape is reduced to just another act of impunity by the warlord’s male deputy—as if it’s in any way comparable to adultery with a grown, consenting woman or defeating an offended man in a battle of charms—with no real bearing on the plot. If the rape was scrubbed from the film, the only difference it would make would be to spare viewers the horrors of sexual violence.

Perhaps, I should not have been shocked at how carelessly Labake Olododo employed sexual assault, having already seen too many instances in Nollywood this year alone. But this was a film about a female warlord in very patriarchal times. And this was a film directed by Biodun Stephen. Very few people in Nollywood have handled sexual violence onscreen with as careful a grip as Stephen did in The Wildflower, her 2022 film about gender-based violence.

In The Wildflower, Biodun Stephen takes on the stories of multiple women living through abuse, from a mother with a physically abusive husband and her teen daughter being harassed by a neighbour, to a young woman who is raped by her boss. When I reviewed the film upon its release, I praised how carefully it handled the “circumstances of the assaults, the antecedents, the subsequent trauma, as well as the responses and reactions of the society, without embellishing or downplaying them.”

It did contain visual depiction, but even that was done with as much dignity as could be mustered in the circumstances. And so, it really did take me by surprise to go from the thoughtfulness of The Wildflower to the recklessness of Labake Olododo.

The gendered reality of these problematic portrayals is as clear as a sunny day, but on occasion, Nollywood flips the script. This year, we have also had a film that shamelessly features child molestation where the victim is a boy and the perpetrator a woman, for the purpose of shock and sympathy farming. The film is Family Brouhaha (2025), a Femi Adebayo-directed comedy about a dysfunctional wealthy family.

Forced to gather for their matriarch’s birthday, long-standing animosities hover in the air around the siblings. Eventually, one of them, who has been taking advantage of a female domestic worker sexually, privately reveals to the family doctor the source of his own bitterness. As a boy, he’d been molested by the female help, and his family had failed to protect him.

It’s such a weighty revelation that the film should definitely address. You’d expect that at some point, the family will confront that history and something useful will come out of its inclusion in the film. But the best we get are a few rehearsed words about healing from the doctor. In Family Brouhaha, child molestation simply becomes not only a ready excuse for an employer who abuses his staff, but also a reason to sympathise with an abuser.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. I’ve watched a film this year that tackles sexual assault differently, with deliberate delicacy and a clear message. Dika Ofoma’s short film, God’s Wife, premiered in Nigeria in late 2024, but I only got the chance to see it at a small screening in April this year. The film follows a young mother named Nkiruka (according to the screenplay, although we never do learn her name in the film) who has just become widowed.

The ways of her people demand that Nkiruka surrender herself to her late husband’s brother, who thinks himself entitled to her. Culturally, a man’s brothers are, in a sense, also husbands to his wife, and in some parts of Igboland, the “Ikuchi Nwanyi” custom allows a man to adopt his late brother’s widow. At first, Nkiruka resists. Then, power dynamics weaken her resolve, basically depriving her of the capacity to consent or refuse. And when she resists again, her brother-in-law graduates to violence.

But the film focuses on Nkiruka, on what her experiences mean for her and on how she deals with them. And throughout the film, Ofoma ensures Nkiruka’s dignity, even as her vulnerabilities are visible. There are no graphic details of the assaults. In fact, in a very intentional subversion of film culture, Nkiruka stays clothed all through, and the only instance of nudity is on the part of the perpetrator. By the end of the film’s fifteen minutes, Nkiruka reclaims her agency in a daring way, and the audience is enlightened and moved to deep reflection.

There is a 2019 Vulture piece that asks: “What Does It Mean for a Rape Scene to Be ‘Done Well’?” Like the Hollywood film she centres her arguments around, the writer, Angelica Jade Bastién, does not provide a definite answer, but she does emphasise “how far we have to go in creating a cinematic language dealing with assault that is truthful, without heaping new trauma on audience and actors”. Similarly, The Atlantic’s Sophie Gilbert, in her essay titled “When Rape Is a Plot Twist”, suggests that there is a way to use sexual assault as a narrative device, “but only if writers and directors are aware of the stakes”.

And the stakes are too high. Sexual violence is real. To pretend otherwise would not in any way change the reality and may even contribute to worsening the reality of it. And so, it will continue to be portrayed on both the big and small screens. But doing so recklessly or unnecessarily also contributes to worsening the reality of it, maybe even more so.

When I read Gilbert’s article (and every piece I’ve cited in this essay makes for important reading), God’s Wife came to mind. Indeed, there is a way to portray sexual violence onscreen, even in Nollywood, and that way does not involve reducing it to a mere exploitative plot device. As Gilbert puts it, “The ones that use the subject for deeper examination rather than cheap twists are the ones that—hopefully—point the way forward”. They, too, are difficult to watch. But they are the only ones that have reason to exist.

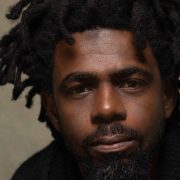

Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku is a writer, film critic, TV lover, and occasional storyteller writing from Lagos. She has a master’s degree in law but spends most of her time watching, reading about and discussing films and TV shows. She’s particularly concerned about what art has to say about society’s relationship with women. Connect with her on X @Nneka_Viv