What unfolds in Pasa Faho is a delicate story about a father struggling to hold on to who he is and what he has, even as he crumbles beneath the pressures of legacy, identity, and obligation under the watchful gaze of his son.

By Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku

There is an Igbo proverb that says, “When the mother goat chews grass, her children watch”. A variation of this proverb is quoted, in Igbo no less, in Pasa Faho (2025), Kalu Oji’s tender debut feature that feels very honestly Igbo even though it is an Australian film set in Australia and written and directed by an Australian born and bred filmmaker of Nigerian descent.

The film’s version of the adage cites a mother hen. But, interestingly, the character whom the mother hen symbolises is a father. And even more interestingly, an actual goat plays an essential role in the film, with the subject of what to feed a goat forming an important part of the conflict between the film’s father and son.

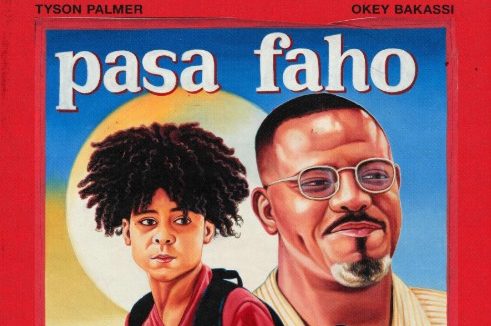

The father, Azubuike (Okey Bakassi), is a Nigerian immigrant with a shoe business in Melbourne. He has had the business long enough for it to be thriving, but instead, the business has been dwindling while financial responsibilities pile up. So, when his attentive and ever-questioning teenage son, Obinna (Tyson Palmer), comes to live with him, though he wants nothing more than to have his son with him, his frustrations start to rise. And it all becomes too much to bear when the lease on the shop he has been renting for a decade comes under threat as the building owner decides to sell to a developer.

What unfolds in Pasa Faho is a delicate story about a father struggling to hold on to who he is and what he has, even as he crumbles beneath the pressures of legacy, identity, and obligation under the watchful gaze of his son, who, in turn, is crumbling under the pressures that his father is trying and failing to shield him from. Oji captures this dynamic with a similarly attentive and observing lens, leaving plenty of room for the characters themselves to explore the edges of their story.

But this is not strictly a tale about a father and son. In Pasa Faho, a play on the phrase “parts of a whole”, Oji builds a small Igbo community, not around Azubuike but simply connected to him. Azubuike is not a larger-than-life character around whom everything revolves. Instead, he is a part of a community constantly negotiating their pride and identity in a foreign land while maintaining an awareness not just of their status as immigrants but also of their place in a bigger cultural society, and while nursing a desire to one day return home.

In this immigrant community that is mostly bound by a shared culture and religion, people are dealing with all sorts of pressures and expectations. Azubuike’s sister, Amaka (Laureta Idika Uduma), is participating in a weekly contest for an all-expense-paid trip to Zanzibar because she wants to physically escape certain pressures that are weighing her down.

A family friend is losing her mind over her daughter’s decision to take a gap year because Igbo people work hard when they are still young. And a teenage girl wants to “level the playing field” and win herself a razor scooter, even if she has to cheat to do it.

Even Obinna has to deal with his own identity crisis and cultural clash. Prior to moving in with his father, he had been living with his white mother in a different part of the country. At school, he goes by an English name he gave himself because it is easier than having people pronounce Obinna.

At home, adults speak Igbo when they mean to keep him out of the conversation (in one instance, when the adults speak over him in Igbo, even the subtitles switch from English to Igbo, to give the audience a sense of the alienation Obinna must be feeling). And when cross-generational conflicts occur, Obinna simply cannot understand why children are supposed to treat adults as if they are always right.

What is particularly interesting is how Oji uses that small community to tell the entirety of the story. Every point of conflict stems from within the community and its broader culture, home and abroad. That Azubuike is a salesman with a shoe business and that he charms customers with comments like “If I sell this shoe to you, I’ll no longer be the best dressed person” are not random, nor is the fact that the tangible conflict relates to land and to clashing ambitions.

But Pasa Faho never overemphasises these cultural qualities in the way that ethnic-leaning films tend to do, nor does it flatten the characters, especially Azubuike, into stereotypes. Instead, Oji imbues the character with the nuances and cultural contexts that tend to shape an Igbo man—particularly an Igbo immigrant who has a son he intends to leave a legacy for—while also keeping him steeped in the culture with elements that are external to him, most notably the music, both the highlife music that Azubuike loves to play, and the additional predominantly Igbo soundtrack that accompanies the film.

In all of this, though, Pasa Faho remains, at its core, a film about a father and son connecting. This year, the world has already seen one splendid Western-funded portrayal of the relationship between a Nigerian father and son, and of a father’s struggle to provide, in Akinola Davies Jr.’s My Father’s Shadow (2025). Pasa Faho is another one, with a different context and set in a glaringly contrasting environment—Oji’s Melbourne is manifestly slower and more passive than Davies Jr.’s Lagos—but a similar core.

So, Pasa Faho makes space for the father and son to indeed connect. Sometimes with jokes and teasing; sometimes over stories and lessons; and sometimes through conflict and harsh exchanges, all of which reflect Azubuike’s efforts to train his son in what he believes to be the ideals of an Igbo man while he, himself, still wrestles with what those ideals mean.

On many of these occasions, blissful or hurtful or a combination of both, the goat becomes the catalyst, triggering a shared understanding, even if temporarily, or creating an even wider chasm between them both.

But the goat also stands as a symbol of both the cultural divide between father and son and the difference in the burden of responsibilities that each shoulders. Where one values the killing of an animal as a celebratory rite, the other would rather give the animal a name and keep it as a pet. And what the father intends as special food in a time of scarce resources becomes, itself, a consumer of food in a time of scarce resources, unsurprisingly translating to a recipe for conflict.

It is also in those moments between father and son that the performances are most gripping. Pasa Faho relies heavily on both characters for the story’s emotional beats, and thankfully, unlike many of the cast members who have not done much acting, Okey Bakassi (who has been acting in Nollywood for decades) and Tyson Palmer are strong enough performers playing a parent and child with an obviously strained relationship but who are finding ways to get along even under stressful conditions.

Bakassi, in particular, does a fine job of channelling those traditional tendencies of Igbo men who are culturally required to project strength and mask weakness, without exaggeration or caricature. And while this comedy drama is more dramatic than comedic, Bakassi’s comedy background as one of Nigeria’s most famous comedians does have its use in the film’s lighter moments. After all, a slow drama can sometimes get too dull, and those entertaining bits can make the difference between fatigue and revival.

In one funny but sad moment, Azubuike tells his annoyed son that for one to eat steak, something has to die. Bakassi’s delivery makes the line stick. But it may also be the single line that encapsulates the essence of Pasa Faho.

Sometimes, you have to sacrifice one thing to enjoy another. Or, as Amaka puts it when Obinna asks why his father, who was a builder before his relocation to Australia, started to sell shoes, “Sometimes you build buildings, sometimes you sell shoes.”

What Amaka leaves unsaid is said clearly by the ultimate story choices that Oji makes in Pasa Faho. Fighting to hold on to the familiar has its time and place, but sometimes, there is strength in letting go and starting afresh.

Rating: 4.3/5

*Pasa Faho premiered at the 2025 Melbourne International Film Festival and subsequently screened at the Chicago International Film Festival in the same year. It had its Nigerian premiere at the Africa International Film Festival (AFRIFF) 2025.

Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku is a writer, film critic, TV lover, and occasional storyteller writing from Lagos. She has a master’s degree in law but spends most of her time watching, reading about and discussing films and TV shows. She’s particularly concerned about what art has to say about society’s relationship with women. Connect with her on X @Nneka_Viv