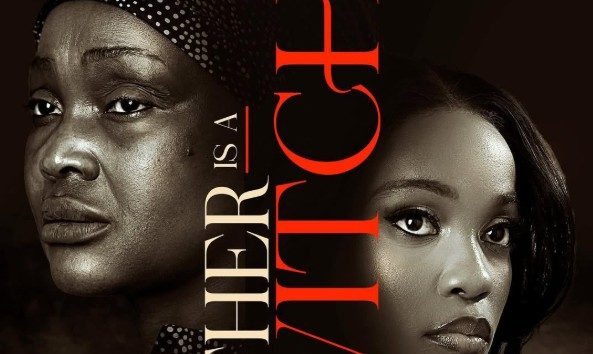

My Mother Is a Witch is one of Niyi Akinmolayan’s most decent endeavours, with strong performances from a leading cast that carries the emotional weight of the film, aided by the film’s sombre tone.

By Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku

When I first heard of Niyi Akinmolayan’s latest release, My Mother Is a Witch (2025), I was reminded of a comment made by Oge Obasi during an Afrocritik interview after the C. J. “Fiery” Obasi-directed Mami Wata (2023), which she produced and premiered at Sundance.

She’d been asked about challenges that came up while shooting the film, and she responded: “We were making a film about Mami Wata. Typically, in Nigeria, we got a lot of ‘God forbid. Are you people Christians? Don’t you believe in God?’” And I immediately felt guilty about how difficult I was finding it to say the title of Akinmolayan’s film.

Yet, being a Nigerian with Nigerian sensibilities, it was a first instinct to dissociate from a title that is essentially a negative statement with such personal phrasing. And it obviously wasn’t just me. When I made a call to a cinema to confirm showtimes for My Mother Is a Witch, the respondent’s first reply was “Your mother” before course-correcting. And when I got to the cinema, both the attendant and I dropped the “My” and avoided the title as much as possible.

But that’s the essence of My Mother Is a Witch, a film that is intended to provoke both thought and discomfort, confronting intergenerational trauma and the weight of familial dysfunction with a complicated mother-daughter relationship at its centre. Mercy Aigbe and Efe Irele bring the mother and daughter to life, leading an appropriately small cast that serves the story effectively.

Aigbe plays the mother, Adesuwa, and Irele the daughter. Her mother calls her Imuetiyan, but she prefers Jess, short for Jessica. When the film opens, we see her first—in the UK where she’s spent twelve years and has built a career in fashion, working with British Vogue. But on the day we meet her, she gets a video message from a doctor back home in Benin, Nigeria. Her mother has passed on, and her last wish was for her daughter’s forgiveness and for a decent burial.

As she lights a smoke in the balcony of her near-lifeless UK flat that she now calls home, you can immediately tell that Jess’ feelings about the matter are much more complicated than grief; that grief might not even be in the picture. Yet, Jess packs a bag to return to the country she once swore she’d never come back to, where condoling neighbours whom she distrusts hover around her and an unpleasant surprise awaits her, and where she’ll eventually take us—and Doctor Ayo (Timini Egbuson)—through her past and the events that damaged both her and her mother.

Writer-director Niyi Akinmolayan (The Man for the Job (2022); The House of Secrets (2023); Lisabi: The Uprising (2024)) has said that My Mother Is a Witch comes from a personal place for him. And you can very easily tell from how intimately he approaches the story, how contained he keeps it, how tenderly he directs it, and how affectionately he captures the dichotomy of home.

Despite the damage that weighs down the characters’ hometown, in Benin, the town is photographed through a loving lens, even if Jess is too preoccupied with the torturous memories to admire it with us. Home in Benin is alive, populated and brimming with personality (although unusually lacking in evidence of catholicism which the film later relies on in its message of confession and reconciliation), a stark contrast to the orderliness and flatness of the UK home she’s desperate to get back to.

But before she can return, Jess—and the film itself—must resolve the internal and external conflicts. So, complications arise that keep Jess stranded in Benin, providing her with opportunities to hash things out and find closure, including confrontations with her mother that she had not expected when she boarded her flight at Manchester.

All familial relationships are complex, but mother-daughter relationships are complex in a way that is fundamentally different from the complexity of, say, father-daughter or mother-son relationships. There’s often a specific layer of tension, informed by gendered expectations, that tends to create a rift between a mother who knows the reality of womanhood in a very gendered society and a daughter who just wants to live.

My Mother Is a Witch has glimpses of that dynamic. Adesuwa’s cruelty and insecurities are triggered by a fear of the possibility that her daughter could end up an inadequately-educated single mother like her, with the accompanying abuse and other gendered disadvantages.

But My Mother Is a Witch does not go beyond glimpses. Instead, it crafts a generic parent-child conflict that is only devastating because it features the worst possible form of parental cruelty. Then, it wraps the conflict in Hollywood teen-speak. While Adesuwa is credible as a Nigerian mother, teenage Imuetiyan (as Jess is called at home) feels like she’s ripped out of a Ginny & Georgia (2021) episode. And so, the conflict, as important as it is and as relatable as it tries to be, sometimes feels too out-of-touch with reality, pulling you out of a film that is supposedly steeped in reality.

It doesn’t help that the opportunities for confrontation that My Mother Is a Witch painstakingly creates are not utilised beyond rehashing the conflict itself. Mother and daughter are put on screen only to remind us that they once loved each other very much and now can’t be in the same room together. And when they’re both finally at a place where resolution and healing can start to happen, the film leap frogs past the stages of reconciliation, moving from deep-seated, decade-old, completely valid anger and hurt to forgiveness and closure in one fell swoop.

There is a beautiful memory montage and an evocative mirror scene which serve, together, as the vehicle through which the conflict comes to a head and is resolved. It’s a sequence that is as tender as it is moving. But it’s also a reflection of the defining problem of this film. My Mother Is a Witch handles its resolution in a way that men think women handle conflict, with one big emotional outburst.

There is no conversation, no real baring of souls, no hashing-out. Just an emotional song anchored by tears from a mother whom her daughter ordinarily believes to be manipulative and self-centred. My Mother Is a Witch forgets that it is a film that deals with women, and women talk.

Still, My Mother Is a Witch is one of Akinmolayan’s most decent endeavours, with strong performances from a leading cast that carries the emotional weight of the film, aided by the film’s sombre tone—at least, until the film undergoes a jarring tonal shift and devolves into a tonal seesaw.

Jess’ internal battles are glaring because of Irele’s demeanour and mannerisms, and Aigbe’s Adesuwa is near-terrifying as a mother projecting her own trauma and insecurities on her naive teenage daughter. Irele and Aigbe clearly prove themselves to be capable of digging into the nuances of the relationship that a film such as this one seeks to explore. Pity that My Mother Is a Witch does not quite succeed in navigating those nuances.

Rating: 3.2/5

(My Mother Is a Witch opened in Nigerian cinemas on 23rd May 2025)

Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku is a writer, film critic, TV lover, and occasional storyteller writing from Lagos. She has a master’s degree in law but spends most of her time reading about and discussing films and TV shows. She’s particularly concerned about what art has to say about society’s relationship with women. Connect with her on X @Nneka_Viv