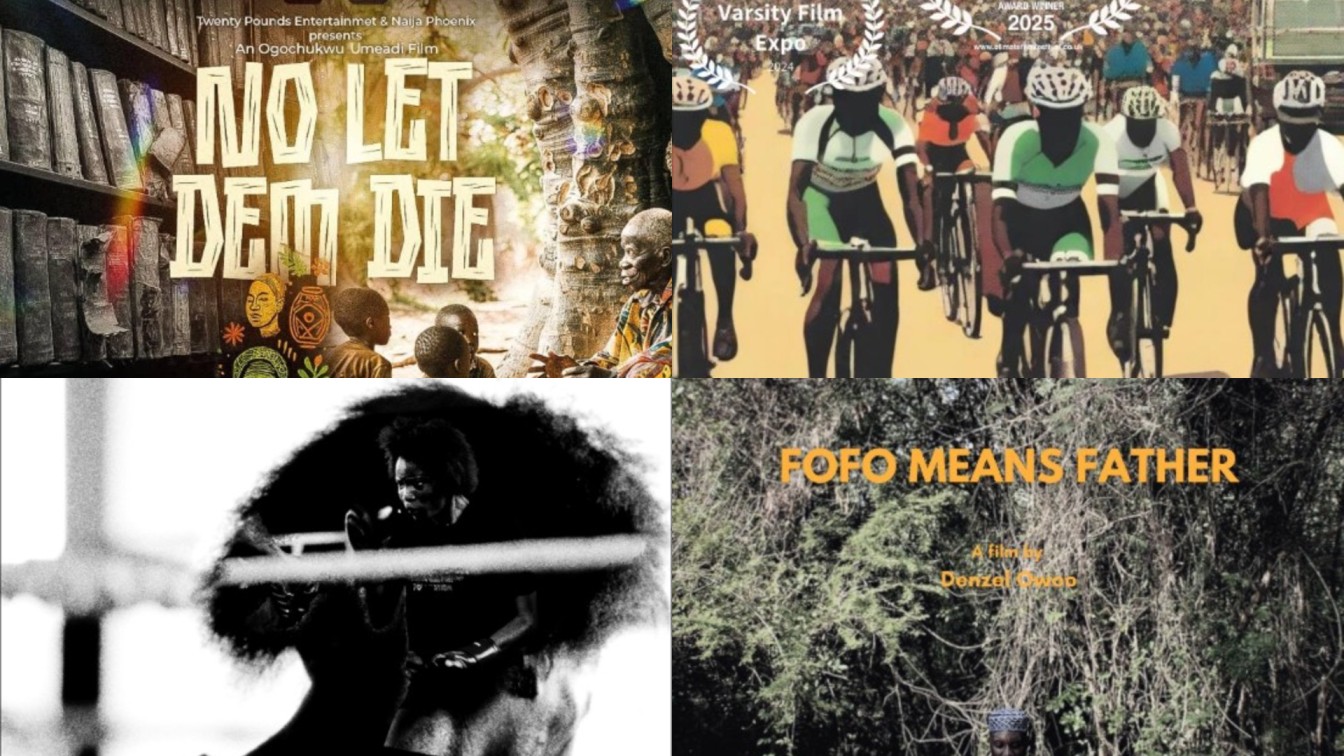

Among the screened films were five documentaries—The Grief, Fofo Means Father, Beyond Olympic Glory, Critical Mass, and No Let Them Die.

By Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku

Founded in 2022, The Annual Film Mischief (TAFM) was established to spotlight and empower emerging independent filmmakers across Africa. In the four years since its inception, the festival has been building a reputation for thoughtful programming, including a special screening of Arie and Chuko Esiri’s critically acclaimed Eyimofe (2020) during its inaugural edition.

The fourth edition of TAFM is currently underway across Nigeria, Ghana, and Tanzania, featuring a diverse slate of officially selected short films under the theme “Reclaiming Self”. Nigeria’s leg of the festival has only recently concluded, running from 16th to 18th October, 2025.

Among the screened films were five documentaries—The Grief, Fofo Means Father, Beyond Olympic Glory, Critical Mass, and No Let Them Die—all of which are reviewed in this first half of Afrocritik’s two-part coverage of TAFM 2025.

The Grief (Nigeria)

Shittu Abdulafiz’s The Grief (2025) sets out to pay homage to the dead, with multiple subjects (drawn from the director’s own family) recounting personal experiences of loss, grief, and moving on. The sample size is understandably small but still wide enough to include a range of losses, mostly of the familial kind.

What stands out is how much the documentary includes elderly people in its exploration of grief, especially in a world where the aged are often excluded from such conversations due to expectations that loss should be familiar to them. In one instance, an elderly woman speaks about the loss of her siblings over the years and the inability of friendships to fill that void.

However, despite the material, The Grief fails to pack much of an emotional punch. It is possible that Abdulafiz had concerns about exploiting his subjects or crossing the line into “trauma farming”, but The Grief is too lukewarm and lacks the technical capacity to evoke the emotions required of a film that tackles a subject as heavy as grief.

Neither is the documentary intended as a dispassionate dive into its theme; it more or less advertises itself as an ode to those who have passed, and it makes no attempt at a theoretical study of grief (there are no expert interviews, for example).

What the documentary succeeds at is in transporting the viewer to a time of personal experience with loss. You may learn nothing new about grief, but, as is usual when listening to others talk about their loss, your own experiences with grief are sure to come to mind.

Fofo Means Father (Ghana)

In Fofo Means Father (2023), directed by Denzel Owoo, Ghanaian filmmaker, Fofo Gavua, reflects on his filmmaking career and his mental health. Five years after his debut, Gavua is in the process of making his next film, and it is against this background that Owoo positions the documentary.

But Fofo Means Father is less about filmmaking itself and more about a filmmaker’s personal journey as a person living with bipolar disorder. The documentary follows Gavua not only on the set of his film, but also to (presumably) his children’s school, and to the compound where he works out.

Yet, much of it finds him sitting in a chair in an empty room, sharing intense and deeply personal thoughts and feelings about how people react to him (especially as a man) because of his condition, about his interest in therapy which he is unable to afford—only two percent of Ghanaians with bipolar disorder get treatment, says the closing title card—and about how filmmaking keeps him alive.

Films about filmmakers tend to be ambitious and technical. Shot on iPhone 11, and with an inconsistency in flow and narrative direction, Fofo Means Father does not exactly fit that bill. But Owoo uses what little visual flair can be found in the serenity of the natural environment and keeps the documentary focused on giving voice to Gavua’s internal struggles.

As Gavua opens up, it often feels like being in his head, and it can be a very uncomfortable watch. Still, that rawness and honesty are the documentary’s strongest elements. The result is an imperfect but poignant reminder of society’s relationship with mental health and masculinity, and a valiant effort at destigmatisation on the part of both filmmakers.

Beyond Olympic Glory (Nigeria)

In 2024, 22-year old Cynthia Temitayo Ogunsemilore set out to represent Nigeria in the Women’s 60 kg boxing event at the Paris Olympics but was disqualified after failing a drug test, an experience that would break her as much as it would build her up.

Beyond Olympic Glory (2024), the well-deserved winner of the TAFM 2025 Grand Cheese Prize for Best Film/Documentary, is Ogunsemilore’s story, with director Shedrack Salami documenting her journey from her local community in Bariga, where she was raised, to the City of Paris, where she had her dreams dashed.

Ogunsemilore takes the opportunity to insist on her innocence and confusion about the circumstances that led to her disqualification, and also on her readiness to continue her boxing career. She is honest and raw, unrestrained in her thoughts but also composed in sharing them, allowing the audience to feel both her disappointment and her determination.

But Beyond Olympic Glory does more than give Ogunsemilore an opportunity to tell her side of the story. It captures her hopes and excitements, and those of her family. And it draws a sharp contrast between Ogunsemilore’s modest training background and the relative ease of training and competing in countries where athletes have access to proper equipment. It is a reminder of the infrastructural weaknesses of Nigerian sports and the country’s endemic lack of a proper support system.

Salami enriches the narrative with interviews from Ogunsemilore’s parents, her local coach, a lawyer with some sports expertise, and an international sports analyst. Together, they paint a fuller picture of the silence and failures of the Nigerian Boxing Federation, and the difficulties that Ogunsemilore has had to endure.

Beyond Olympic Glory does not provide answers to the doping allegations levelled against Ogunsemilore, but that is part of its truth. Answers remain elusive because no real investigation has ever taken place. The athlete has neither the financial capacity nor the institutional support. What emerges, instead, is a moving story of resilience in the face of neglect, a story of a young woman undeterred from fighting for her dreams even when the system is set up to hold her down.

Critical Mass (Kenya)

In Nairobi, there is a cycling movement called Critical Mass, aimed at promoting sustainable mobility. Alex K. Maina attempts to briefly document this movement in the short documentary titled Critical Mass, with interviews from participants, especially women.

But Maina’s documentary feels like a random edit that drops the audience in the middle of an event and cuts off the experience before they have had a chance to make sense of it. Perhaps, regular participants of Critical Mass may find some value in this documentary, but everybody else may be better off taking advantage of the internet.

No Let Them Die (Nigeria)

In No Let Them Die (2024), writer-director Ogochukwu Umeadi makes a case for intentionality in the preservation of elements of culture across Nigeria, from fashion to music, art, language, and even traditional medicine.

For this purpose, Umeadi intersperses video clips and archival footage, supported by spoken word voiceover in Nigerian Pidgin, with interviews featuring a broad range of contributors—academics, archivists, officials of related government institutions, leaders of non-governmental organisations, local artists, and business owners.

The documentary also explores the weak infrastructure available for cultural preservation in the country, from dilapidated libraries to the poor preservation culture of the country’s archival institutions, which sometimes deliberately destroy archival materials. “There are some that they purposely destroyed by themselves,” one archivist says. “These are historical materials, and they used their hands to destroy them.”

No Let Them Die is yet another exposé on Nigeria’s systemic neglect, with a cursory look at some of the social factors that have triggered or contributed to the country’s continuous loss of heritage. It struggles with narrative structure and misses the opportunity to preserve local languages by having some interviewees, at least, speak in their dialect. But it certainly serves as an important reminder of the loss of collective history and the eternal value of preserving recordings of memory.

Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku is a writer, film critic, TV lover, and occasional storyteller writing from Lagos. She has a master’s degree in law but spends most of her time watching, reading about, and discussing films and TV shows. She’s particularly concerned about what art has to say about society’s relationship with women. Connect with her on X @Nneka_Viv