The fourth edition of The Annual Film Mischief (TAFM) remains in progress across Nigeria, Ghana, and Tanzania, featuring a diverse slate of officially selected short films under the theme “Reclaiming Self”.

By Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku

The fourth edition of The Annual Film Mischief (TAFM) remains in progress across Nigeria, Ghana, and Tanzania, featuring a diverse slate of officially selected short films under the theme “Reclaiming Self”.

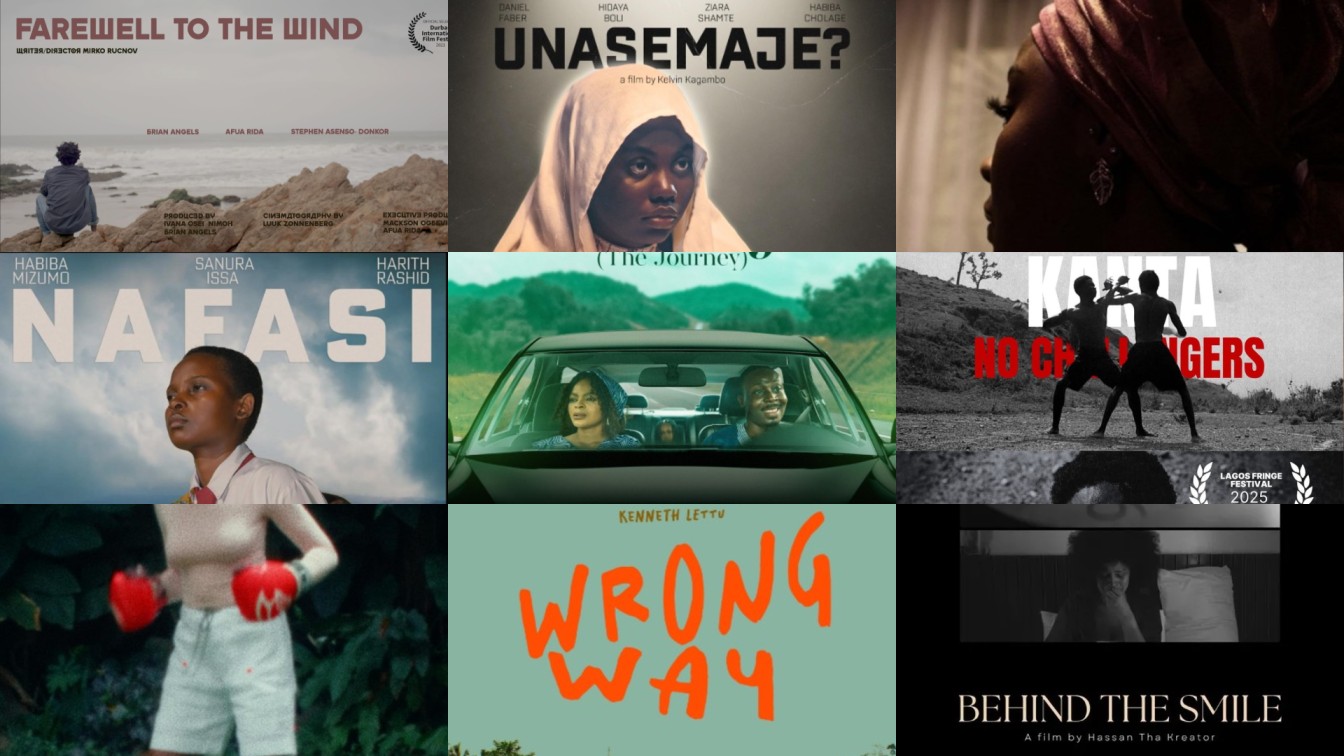

In the first half of Afrocritik’s two-part coverage of TAFM 2025, we reviewed documentaries screening at the festival. In this second part, we review non-documentary films, both narrative and experimental fiction, screening this year: Kanta: No Challengers, Behind the Smile, Ìrìn Àjò (The Journey), Unasemaje?, Tell It No More, Wrong Way, Cause, Effect & Maybe Consequences?, Barely Making Much, Zawadi Ya Mjomba, Nafasi, and Farewell to the Wind.

Kanta: No Challengers (Nigeria)

The concepts of perpetual war and internal conflicts are personified in Kanta: No Challengers, a Hausa-language short film by writer-director, Gbolahan Qudus Laniyan, where a young man fights endlessly, whether he has an opponent or not.

Kanta: No Challengers is essentially an eleven-minute play on fighting without ceasing and without reason, inviting the audience to question their choices, sit with their internal battles, and interrogate their reasons for maintaining certain stances, and whether those reasons even still exist.

But while Kanta: No Challengers is technically impressive for a filmmaker still relatively new to the art, Laniyan appears unsure of the capacity of his audience to understand the subtext, so the short relies heavily on voiceovers and onscreen texts that lay on the message too thick.

Comments like “Choose your battles lest they choose you” and “I didn’t choose to be born, so how can I choose how to live?” are littered across a fight sequence that stretches through the runtime. The idea is evident, but the film ends up feeling too bare and too overladen all at once—a contradiction that mirrors its struggle to balance vision with substance.

Behind the Smile (Nigeria)

Shine Rosman and Bobby Ogbolu star as placeholder characters in Behind the Smile (2025), a frail short film about depression directed by Hassan Tha Kreator. Ogbolu, who doubles as the writer, plays Damola, an obviously depressed man locked away in his room and unable to return to his place of work until one evening when, in the course of his other job as a rideshare driver, he picks up a generous passenger who tips him after overhearing him lament about his money problems.

Rosman plays Ada, the kind passenger, a social media influencer whom we meet before the encounter in the car. The film’s title is clearly derived from her share of the story because she is the character with an inkling of a smile. And the film stays with her most of the time, following her through her day as she gets up from bed in the morning, makes social media posts on her phone, moves around her kitchen, sits behind her laptop, and gets dressed to go out in the evening.

The essence is to show that she is an ordinary person who may not be presenting as troubled, let alone clinically depressed, but it’s quite frankly too tiring to sit through. It is too much wandering with no real substance, and it is as forceful as the literal colour-flipping that the film undergoes when the rug is finally pulled from under to reveal the truth “behind the smile”.

Unlike Damola, who is introduced and sustained in monochrome colouring, Ada is initially painted in bright colours before the film reverts to monochrome. Even their complexions, perhaps unintendedly, reflect this outward presentation that the film is eager to emphasise.

That stylistic choice to hammer on contrast (also noticeable in the stylish font adopted for the film’s title card and opening credits) turns out to be jarring, distracting, and as surface-level as the film and its characters. Behind the Smile seems excited at the prospect of creatively portraying a subject of great depth. It’s a pity that it is little more than a hollow attempt.

Ìrìn Àjò (The Journey) (Nigeria)

In Ìrìn Àjò (The Journey) (2025), produced, written, and directed by Myde Glover, Manuel (Timilehin Ojeola) and Trish (Nneoma Onyekwele), a young couple, embark on a trip with their daughter to meet Trish’s estranged parents. As they head to their destination, Trish becomes increasingly restless. And when they finally arrive, it becomes clear that things have not been as they have seemed.

A popular concept in African spirituality, particularly Yoruba spirituality, serves as a pivotal plot twist and the core of the story. It would have been fascinating if it were new to the screen, but it is a concept that has been considered in several films, especially Yoruba films, and even as recently as My Father’s Shadow (2025) (although in a slightly different form). Ìrìn Àjò approaches it plainly, with no attempt to stand out from other films that have told the same story.

Nonetheless, the film is carried by its leads, especially Onyekwele, who does remarkable work in channelling the uncertainty and suspicion that comes with her character, as well as the steady hands of a promising filmmaker. Glover is known for his AMVCA-winning MultiChoice Talent Factory project, Everything Light Touches (2025). He could be bolder with his vision, but he is undoubtedly having a decent start.

Unasemaje? (Tanzania) 2024

Writer-director, Kelvin Kagambo, presents a minimalist Tanzanian re-imagining of the immaculate conception in Unasemaje? (2024). A maiden named Mamu has been handed over to a respected woman to prepare her for her marriage to Yusufu. However, before the marriage, Mamu is found to be pregnant even though she swears she has not been intimate with any man. Of course, her situation is dire in the average traditional community, but in her coastal village, much like the biblical Israel, the penalty is death.

But there are no angels in this story. Instead, Mamu is surrounded by her mother, her fiancé, and the woman to whom she was entrusted. With all parties around the table, a conversation ensues, marked by quarrels, impatience, and disagreements on how to best approach the circumstances and avoid the consequences. At some point, the question lands on Yusufu’s side of the table, and like Joseph, he is surprisingly understanding. But Mamu herself, played immersively by Hidaya Boli, is never given the opportunity to speak.

This is what makes Unasemaje? potent, not just its peek into purity culture but its portrayal of the silencing of women in decisions that affect them while emphasising that even the well-meaning members of society contribute to the perpetuating of misogynistic systems.

Tell It No More (Nigeria)

The tradition of female endurance in marriage is the bone of contention in Tell It No More (2025), a short film directed by ‘Chukwu Martin and produced by the young filmmaking couple, Wumi Tuase-Fosudo and Temilolu Fosudo (also the writer).

The film’s leading woman, Darasimi (Martha Ehinome), is a reticent and heavily pregnant wife married to an unreliable husband (played by Temilolu Fosudo), and forced to confront the lessons on marital patience that have been passed on from her grandmother to her mother and, then, to her.

As serious as that sounds, Tell It No More manages to be a funny and almost casual watch, unsurprisingly so, given that a sizable amount of its runtime is dedicated to a scene at a hairdressing salon where Darasimi and her unmarried hairdresser, Itunu (Wumi Tuase-Fosudo), debate the value of marriage to women.

It is a setting that is more typically featured on Black American screens but is actually quite realistic and effective within the film’s Nigerian context, setting the stage for a non-confrontational discourse around infidelity, marriage, and the societal expectations shouldered by married women.

Ultimately, when a painful discovery at the salon demands that Darasimi deal with the cracks in her marriage (including with a damning but slightly funny one-liner straight out of How to Get Away with Murder (2014), complete with the accompanying cliffhanger), the filmmakers opt for an open-ended conclusion, highlighting the social difficulty in confronting such situations.

Tell It No More wraps as an important albeit inadequate exploration of its chosen theme, but what it very easily achieves is to trigger conversations about the extent of female patience and the skewed nature of marriage in a patriarchal society like Nigeria.

Wrong Way (Ghana)

“Actions have consequences” is the sole message of Nana Kofi Asihene’s didactic short, Wrong Way (2025), where the proverb “don’t throw stones in the market; it may hit your mother” is translated to film with a few modifications.

The man is Manan, an armed robber whose involvement in crime is apparently rooted in his need to provide for his loved ones, until one of his attacks results in an accident that hits home in a way that completely defeats the purpose of his choices.

But that is really all this film is, a literal moral lesson and nothing more. There is no dramatic weight, and at no point do the stakes feel particularly high. Neither is there any storytelling approach or filmmaking finesse that makes this film more interesting than the many sayings that make the same point. Without question, Wrong Way delivers its message clearly, but with little else to hold on to, it is quickly forgotten.

Cause, Effect & Maybe Consequences? (Nigeria)

The winner of the 2025 TAFM Audience Cheese Prize, Cause, Effect & Maybe Consequences?, is a refreshing sci-fi comedy short film that plays out like the pilot episode of a semi-autobiographical fiction series about a young man tormented by the ghosts of his future and his past, with infinite potential for expansion but not enough substance to ground it yet.

A confident one-man cast and crew, Cheyi Okoaye plays three versions of himself: “Present Cheyi” who lies in bed carefree and unbothered; “Future Cheyi” who has time-travelled from the future with a message that he cannot remember, and now has to convince his younger self to correct bad habits that could possibly threaten their future; and “Weird Cheyi”, who is visiting from the past with habits that even Present Cheyi cannot stand.

All three versions are placed within the limited space of Present Cheyi’s bedroom, where they engage in conversation but on varying wavelengths. Future Cheyi takes things seriously, Weird Cheyi is more interested in fooling around, and everything is casual banter to Present Cheyi. Their dialogue is cheeky and sometimes corny, but mostly in a good way. And their dynamics reflect the contrasts within the self, both at each point in time and over a period of time.

But time constraints are mostly irrelevant to Okoaye’s onscreen personalities, especially to the past and present versions. In fact, Cause, Effect & Maybe Consequences? does not concern itself with the rules of time travel, although it is very much aware of those rules and even mines them for comedy.

In one instance, Present Cheyi says he wants to kill Weird Cheyi, so he asks Future Cheyi, “What’s the rule about that?” Future Cheyi’s answer is telling “Who the fuck knows?” Okoaye may still be unsure of what the rules are in the interesting world he is clearly just starting to build, but at least he knows that there is a lot more that he could do with this idea.

Barely Making Much (Uganda)

“In the stillness of inertia, I find comfort. I take a break, choosing to do nothing”, says the opening line of the spoken word voiceover that accompanies the scenes of Barely Making Much (2024), written and directed by Ian Nnyanzi. But the film’s characters do not do nothing, unless one considers the mundane to be nothing.

The characters are two unnamed girls (played by Antonette Nasike and Ajatum Mercy) with observably distinct personalities. Nnyanzi follows them through a seemingly uneventful day, finding beauty in the nature that surrounds their home and in their cosy but undefined relationship.

One is agile and active, taking interest in activities like boxing and physical exercises, while the other is more inclined to sit in a chair with a book or to stand in front of a mirror applying lipstick, though she does not mind assisting the former in her exercises. The audience sits with them while they drink tea, play Omweso (the local mancala game), and take turns pouring out water for the other to wash her hands.

By nightfall, however, the course changes. “Once you begin to manifest yourself, they see your truth,” says the voiceover poet, just before the girls’ hidden truth, an apparent evil, comes to light.

Nnyanzi appears to be attempting a juxtaposition of the mundanity of domestic life with humanity’s capacity for evil, an effort that calls to mind Jonathan Glazer’s Zone of Interest (2023). Barely Making Much does not quite translate that idea as clearly as it hopes, but Nnyanzi’s direction ensures that the film holds attention and maintains its intrigue till the end.

Zawadi Ya Mjomba (Uncle’s Gift) (Tanzania)

In Fadhili Meta’s Zawadi Ya Mjomba (2025), Swahili for “Uncle’s Gift”, a boy who does not like biscuits accepts a biscuit from his uncle because he believes that rejecting gifts from elders can turn a child into a crow. With this somewhat comedic story, Meta examines not only the dangers of certain superstitious beliefs, but also the effects of authoritarian parenting on children.

The image is painted from the onset. Two boys, Piu and Zuberi, sit for a meal with their mother, but her initial approach to them is inexplicably hostile. When they hear a knock at the door, her instructions to them are swift and insistent, though none of them knows who stands at the other side of the door. The boys are to put on their best clothes, and as they rush in and attempt to comply, they do so with a lot of sneaking about. It is immediately obvious the nature of the sons’ relationship with their mother.

It turns out that the visitor is just their uncle, who typically brings them gifts—biscuits, to be precise. He seems like an easy-going person, the kind of uncle that a boy can comfortably tell that he does not like biscuits. And when Piu, the boy who does not like biscuits, finally opens up, falling to the ground and begging not to be turned into a crow, to the amusement of his audience on and offscreen, the uncle is quick to ask what he would have preferred.

The context is striking. Here is a boy who cannot express the simplest thing to the adults in his life because he lives in fear of their reaction and potential repercussions, reinforced by superstitious beliefs likely also spread by adults to keep children in line. And that is an important message to take from Zawadi Ya Mjomba, a simple and funny but quite relevant short lesson on how self-expression is stifled by the authoritarian parenting methods that are very common in African households.

Nafasi (The Chance) (Tanzania)

When her mother’s attempts to re-enroll her in school are met with resistance, Asia, a teenage mother, takes matters into her own hands in Sudi Mohamedi Masomwa’s Nafasi (The Chance) (2025), produced by Her Education Foundation, a feminist organisation that advocates for equality in access to education in Tanzania.

A campaign film that manages to avoid sensationalism, Nafasi exists to motivate girls in similar circumstances not to give up on education, and to encourage their families to provide them with support. For this purpose, the film focuses solely on the efforts of Asia and her mother in pursuing Asia’s education, the pushback, stigma, and ridicule that they have to confront, and their eventual success against all odds. As such, the fact of Asia’s motherhood does not get any attention outside of Asia’s fight to resume school.

This approach may be the film’s deepest weakness, as it shies away from the reality of motherhood. There are undeniable difficulties that a girl will have to deal with in being both a student and a mother, even when she has support. It seems more honest to acknowledge those challenges while emphasising that they do not have to be an end to a girl’s dream.

But the approach also proves to be the film’s greatest strength. This story is about Asia, and so, Nafasi centres her in it. Her past and the baby’s history are completely ignored and treated as irrelevant. The message is made clearly: returning to school should not be an impossibility for any teenage mother, regardless of how she becomes one.

Farewell to the Wind (Ghana)

The TAFM 2025 Jury Cheese Prize winner, Mirko Rucnov’s Farewell to the Wind (2021), centres on Kwame, an artist and photographer studying the politics of his father’s era—particularly Ghana’s involvement in the Non-Aligned Movement alongside Yugoslavia—with music selections, video clips, and audio recordings offering glimpses into a historic period. Meanwhile, Kwame has also set his mind on a perilous journey across the sea, leaving behind a relationship that holds special significance to him.

It’s rich material that invites deeper exploration, but Rucnov devotes too little attention to the story that he chose to tell, overfixating instead on the film’s aesthetic and stylistic experimentation.

Undeniably, there are artistic choices that are fascinating, especially in the shots and gestures that capture Kwame’s attempts to hold on to memories of his father. But the film eagerly falls into a familiar trap of experimental cinema: sacrificing the story in an almost obsessive bid to present as avant-garde.

Granted, experimental films can function for non-storytelling objectives. But when a story is clearly intended, then there ought to be a balance between actually telling the story and experimenting with the medium—a balance that Farewell to the Wind does not quite achieve.

Vivian Nneka Nwajiaku is a writer, film critic, TV lover, and occasional storyteller writing from Lagos. She has a master’s degree in law but spends most of her time watching, reading about and discussing films and TV shows. She’s particularly concerned about what art has to say about society’s relationship with women. Connect with her on X @Nneka_Viv